The world of living things

Would you like to know the answer? Well, I'm going to tell you anyway. But first, the question. Of all the works of His hands, from slugs to bugs and moss to albatross and everything in between, which of all His creatures does God feel the most affection for? The story goes that the distinguished British biologist, J. B. S. Haldane, when asked by a theologian what one could conclude about the nature of the Creator from a study of His creation, answered, "An inordinate fondness for beetles”.

Haldane’s logic was simple, basing it on the idea that God would make more of the things He liked best. Over 350,000 different beetle species are known worldwide, making up 40% of all insects and eight times as many species as there are fish, amphibian, reptile, bird and mammal species combined. After beetles, His next love is flies! He made over 150,000 different kinds of them.

Why did God create such a huge diversity of living things, both animal and vegetable? Well, nobody can provide a “thus saith the LORD” answer, but we can hazard a jolly good guess.

Why so many kinds of animals?

Evelyn Hutchinson asked this very question in a landmark 1959 paper titled, “Why are there so many kinds of animals?” What did he attribute the staggering biodiversity to? To a corollary of evolution, of course. Arguing that every plant species that exists can form the basis of a number of food chains in which a small plant-eating animal, such as an insect, can be eaten by a larger carnivore, such as a cuckoo and so on up to four or five levels of predator, he concluded that each plant species can provide the basis for the existence of numerous animal species.

On top of creatures with jaws, such as birds, amphibians, reptiles and mammals that munch externally on hapless prey, you have those perfidious parasites that live in or on another creature and dine on their vitals. Virtually every species of animal that exists provides food and lodging for at least one parasitic species. You also have detritus feeders, such as crabs, which scavenge on rotting plant and animal remains. The gooey carcass of just one species of fish could provide a hearty repast for a large number of detritus-eating species, the actual number of such species being limited by the finite biomass of available sludge and by population dynamics.

So his answer to the question of why so many species of animals exist is very simple — evolution has thrown up such a huge variety of plants! Hutchinson then poses the obvious question, “Why are there so many kinds of plants?” To that question, he has no definitive answer.

Intriguingly, terrestrial fauna vastly exceeds marine fauna for diversity, a fact which is put down to the much higher diversity of land plants than of marine plants. A larger number of plant species allows for a higher number of species of animals that eat those plants.

To what do creationists attribute such staggering biodiversity? Simple. God decided how many different kinds of plants and animals to create. Why so many? The proposed answer may sound simplistic, but it’s not: to demonstrate His infinite genius, of course:

For since [as a result of] the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead… (Rom 1:20).

To impress upon us even more forcefully that His capacity for invention, novelty and design is endless, God stretched out creation of living things over millions of years, during which time He stocked our planet with one assemblage of flora and fauna after another. (Since Earth is rather small, it could not support everything that has ever plied the seas or graced the ground all at the same time.) See, for example, Fascinating Furred Creatures of Australia’s Past. Blessed are the eyes that see His hand at work.

He achieves the same end in real time by having created discrete assemblages of living things that are separated from one another by geographical barriers that prevent intermingling. God could have plopped Australia’s unique fauna into the midst of Africa’s distinctive assemblage. You can guess the headline; Mayhem and Murder Hit Africa. And it wouldn’t be a case of kangaroos kicking lions to extinction.

Bigger and smaller

People extol the genius of microengineers. One can understand why hearts beat faster and songs of praise rise in the ether when a miracle of microengineering goes on display. “Ten Incredible Micro-Robots” will surely give you a zing. In truth, what amateurish, clumsy, jerry-built, shoddy pieces of junk they are. Staggering sophistication and intricacy of design that would make microengineers blush with embarrassment is all around you in places you would least expect. Is a fly or a mosquito buzzing around? If so, you are in the presence of greatness — of design, that is. What are you looking at here? An exotic flower? An alien from Andromeda? Those versed in insect lore would probably identify the claws as belonging to an insect foot (tarsus). If you guessed “mosquito”, proceed to the top platform to receive your gold medal.

The image shows the end of a mosquito's leg, including a claw, scales and the pulvillus, a pad with adhesive hairs… these scales dot the entire bodies of mosquitos but are particularly dense near the foot, and may help protect the limb and enable the mosquito to land on water, where these insects lay their eggs. (What in the world is this?)

The photographer, Stephen Gschmeissner, says, "Insects are fantastic… because they have all this sort of fine microscopic details". This next image by the same microscopist of a snippet of the antenna of one beetle species illustrates his point further. Every tiny structure on both mosquito foot and beetle antenna has a purpose. Taking away a handful of scales from the mosquito foot may prove injurious to its health. (Yes, I know. Why did God create mosquitoes?)

Yes, indeedy, if we had but the eyes to see detail at this scale, we would be bowled over by both the refinement of design and the raw beauty of every part of every tiny creature, even a blowfly. The mind of God knows no limits, hence the Revelator’s encomium:

You are worthy, O Lord, to receive glory and honor and power; for You created all things, and by Your will they exist and were created (Rev 4:11).

Next time you swot a mosquito, give a thought to what you have destroyed!

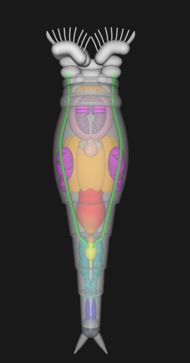

Take one more example of a precision engineering wonder to behold: the microscopic mouth parts and mastax of a rotifer. Members of the Phylum Rotifera are abundant in freshwater bodies and in watery films around soil grains. They are recognized by the presence of a crown of cilia, the corona, around the “mouth”.

So much life in a pinprick!

Glossary

Cilium (pl. cilia): Microscopic, bristle-like filament present on surfaces of many cell types and capable of whip-like motion. Functions in locomotion and in creation of currents in water.

Morphology: The study of structure of cells, tissues, anatomy or gross structure of an organism.

Genome: The totality of genes in a set of chromosomes; the sum of all different genes in a cell.